By CMSgt Paul B. Smith (ret)

Since the beginning of organized warfare, symbols have played an important part in rallying troops to action. Color bearers have willingly sacrificed their lives, time after time, to carry their nation’s symbols into battle so their pride and purpose is clear to all. The willingness to fight, and if need be, to die for a cause is often immortalized on a badge. We in the ammo community have a symbol too. However, like so many other customs and traditions, symbols can lose meaning without a periodic refresher.

Troops have always taken pride in their specific duty in the military and it has been traditional to create symbols with which to identify themselves with. Pilots and aircrew members are recognized by the symbol of a bird’s wings on their chest. These wings are a representation of flight. Our badge represents that which we work with – and that is BOMBS.

We are members of a unique and very old profession and have an equally unique symbol with which to identify. Everyone seems to have heard a different story regarding the origin and meaning of the U.S. Army ordnance badge. Some refer to it as the ‘piss pot’.

The phrase ‘piss pot’ comes from ‘pitch pot’. Pitch pots were a very familiar sight to most everyone in the United States for many years. Pitch pots were round iron or steel bowls filled with pitch and a small vent at the top for lighting. Pitch is a slow burning tar like substance. They were in reality lamps that would burn for many hours and used to mark construction or dangerous areas in roadwork to avoid in hours of darkness. But since the old AMMO symbol on their uniforms resembled these pitch pots, Army AMMO troops started calling it the pitch pot badge. And it wasn’t until relatively recently (late 1960’s during the Viet Nam War era) the word ‘pitch’ was crudely transformed into the word ‘piss’.

All of us in the ammo community have come in contact with this insignia in one way or another. There are even varying speculations as to what the ball with fire shooting out the top actually is. Hopefully, this pamphlet will clear up some of these questions and provide a quick refresher on an important aspect of our ammo heritage.

First we must clear up a most obvious question. What does the object of this symbol depict? It is an early hand grenade from 15th century France that is in the process of blowing up. We in the munitions career field have a direct relationship to this grenade in more than symbolism alone. The thrown bomb or grenade was the beginning of all munitions.

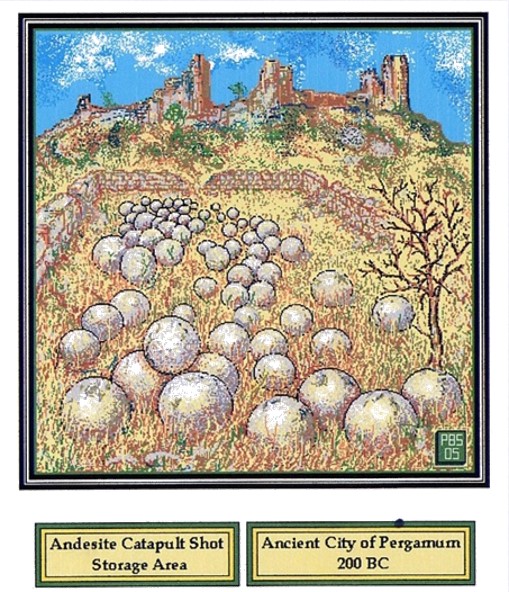

But before we continue, we need to follow the river to its origins to attempt to fully understand the beginnings. Take for example the missile that has its geneses from the spear or javelin. And our shape is no exception. If our symbol has its roots with the grenade then where did the grenade shape have its beginnings? It all began in pre-written history antagonists started throwing stones and rocks at one another. And it was learned by trial that the rounder and smoother the rock the more accurate the projectile. And that is where our ordnance insignia first got its shape. Solid shot cannon balls from the 13th century got its shape from the catapult balls from the 3rd century BC.

Nine hundred rounds of andesite shot of various calibers for catapults were unearthed from a “munitions” storage area at the site of the ancient city of Pergamum. The site dates back to the Hellenistic period (334 BC to 133 BC). Even though these were not explosive rounds they were the weapons technology of the era and where our symbol has its rudimentary beginnings.

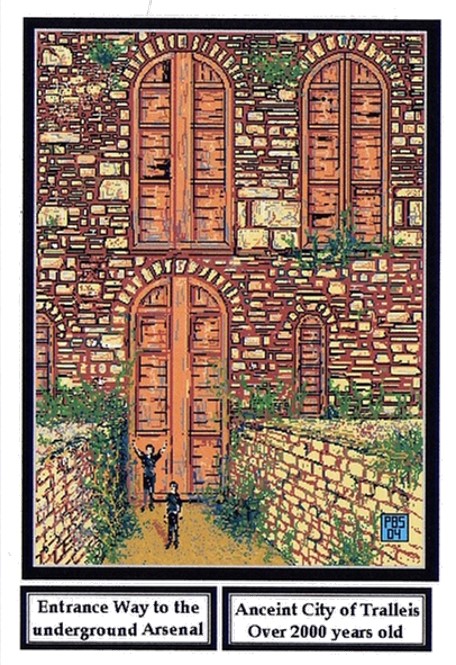

The author had the privilege of entering the underground arsenal at the ruins of the ancient city of Tralleis located in western Turkey. The fortified storage tunnels were used from the Hellenistic era (334 BC to133 BC) through the Byzantine period (330 AD to 1282 AD). Archeologists have discovered smooth catapult balls made from marble within these dark catacombs.

Today’s AMMO troops are carrying out the same basic duties, as did these ancient warriors of over 2,000 years ago in weapons maintenance, storage and delivery.

Now progressing to more modern times. As soon as the Chinese, roughly in the 4th century AD, discovered the effects of burning the composition now known as black powder, the bomb was invented. Although made from only crude bamboo joints filled with black powder, its value as a defensive or as an assault weapon was soon realized. Eventually glass, clay and earthenware were used as some of the early materials these small bombs were made from. Recently the remains of one of Kublai Khan’s war ships, lost in 1281 AD, was discovered off the coast of Japan with ceramic projectiles containing gunpowder and iron shrapnel.

France is believed to be the first to make use of iron to build these small bombs. The 15th century French throwing bomb was constructed in three sizes: a three, two and a one-and-one-half pound iron sphere with a vent for a fuze. This iron ball was filled with gunpowder and pistol balls, which were used to create a deadly fragmentation effect. Soldiers in typical fashion began calling these bombs something totally unrelated to their true function. The bullets within the sphere reminded them of the seeds inside a pomegranate fruit. In middle French pomegranate is pronounced grenade. Thus the word grenade became synonymous with the small throwing bombs. The brave troops whose duty it was to carry a satchel full of these along with a slow burning match to light each bomb, were called grenadiers.

The value of this new weapon soon spread throughout Europe and Asia until there was no formidable army on earth, which did not include special hand grenade units in their ranks.

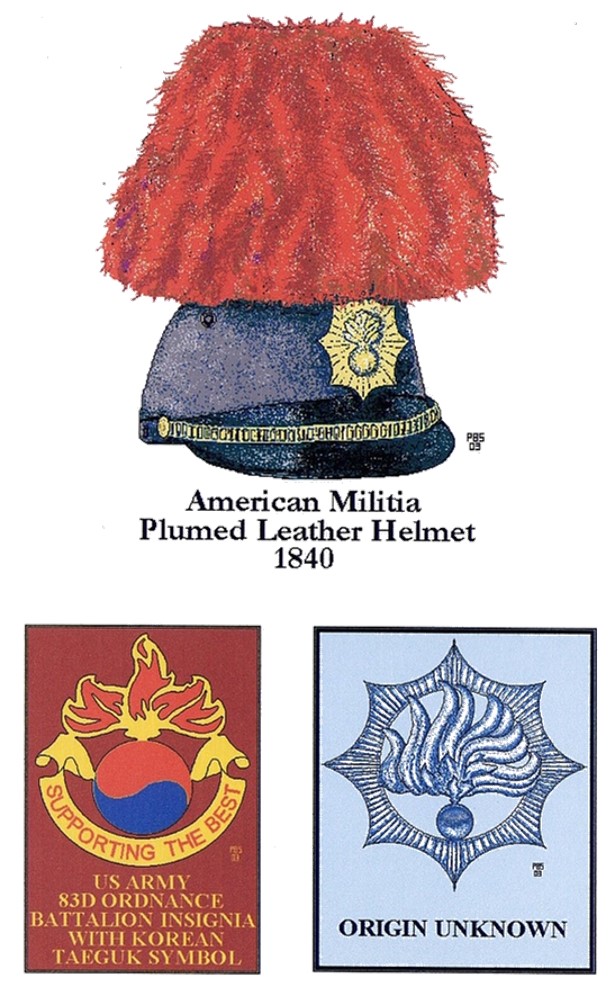

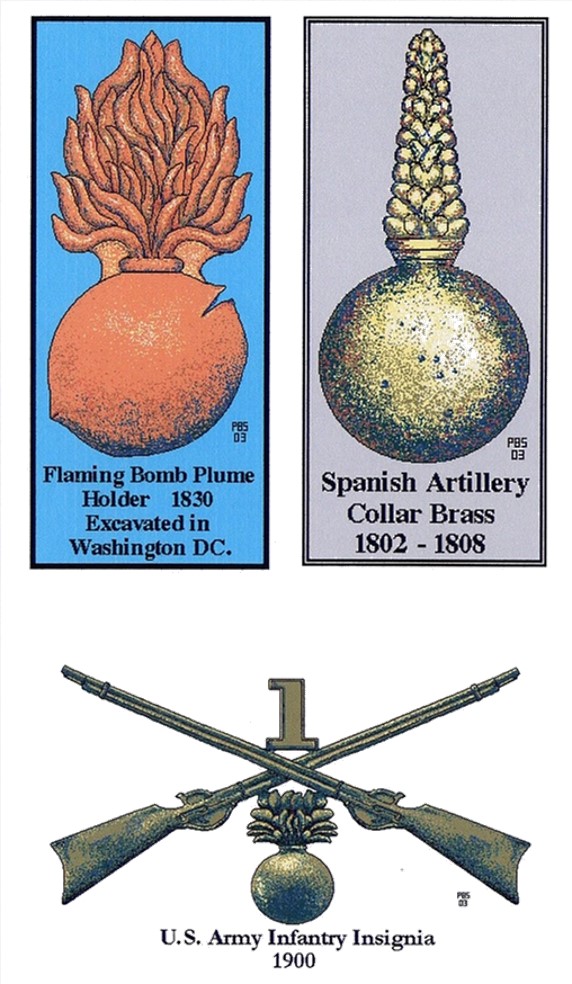

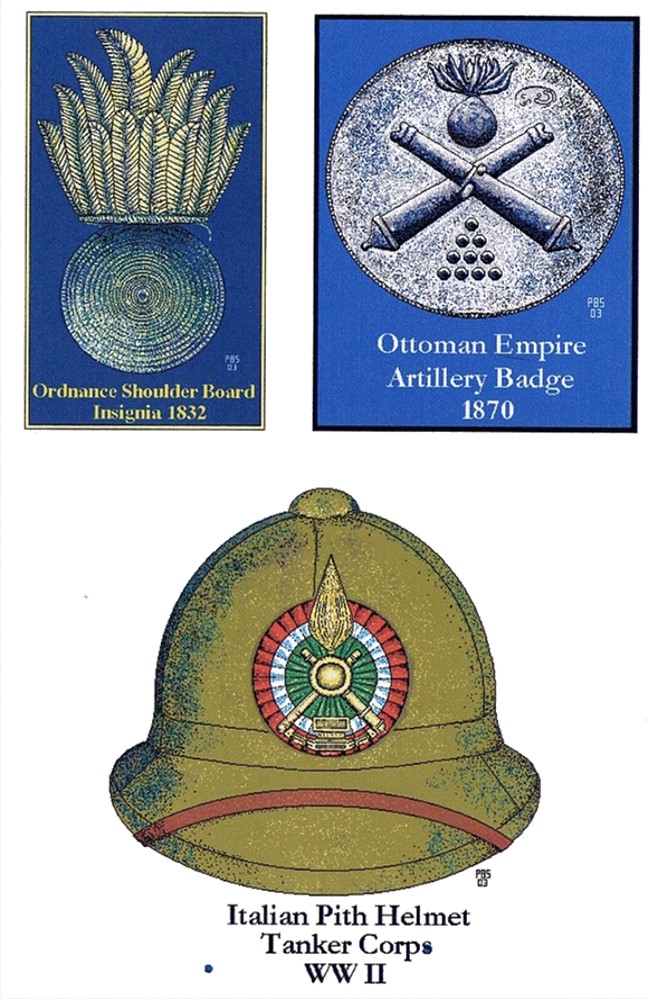

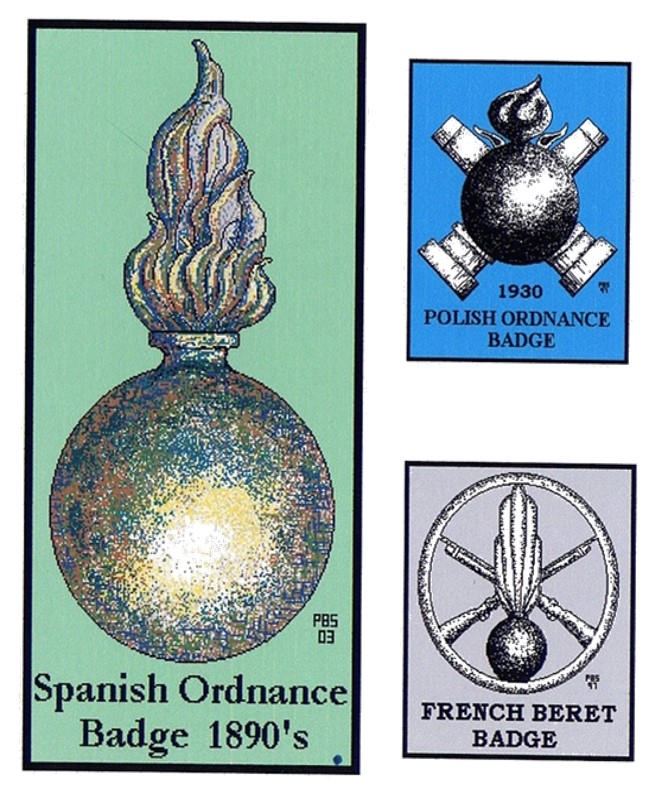

European countries were the first to use the symbol of this grenade on their uniforms. Our emblem began to show up on French and British uniforms around the late 17th century. It has been a distinctive part of military uniforms in several European nations for roughly 400 years. It became prominent and spread throughout Europe in the beginning of the 19th century. Italy seems to have adapted this symbol as the main theme for several different combat duties. Assault regiments, dragoons, tank regiments and the Italian grenadiers, to mention a few, all used the flaming bomb in some form. Today, Italy uses a very ornate bomb symbol on the hats of their Carabinieri paramilitary forces. Poland also uses the little bomb for the military police and artillery officers. The Polish ordnance units use a bursting bomb in front of crossed cannons. Great Britain is another country, which uses this symbol for many different military duties. In World War I (1914-1918), British uniforms are seen with the “bomber’s badge” on the right sleeve.

Turkey is a country that uses the symbol exclusively within its Army. At the entrance of each Turkish Army base, to include one on the island of Cyprus, there are large cement versions of the flaming bomb at the main entrance as well as along the outer walls of the complex. Within an Army HQ compound in the capital city of Ankara all the street lamps are in the shape of the familiar piss pot.

In modern day Switzerland, only the elite infantry grenadiers trained in demolitions, flamethrowers, and other special skills are authorized to wear the flaming bomb on their collar. The famed French Foreign Legion, whose presence has been throughout Asia and Africa for generations, have a unique seven-flamed bursting grenade on their berets. Iraqi as well as Israeli ordnance personnel wear our symbol. As you can see, space does not permit mentioning all the different nations or the various duties associated with wear of the flaming or bursting bomb.

The symbol first came to our shores on the uniforms of French soldiers fighting during the long struggle for possession of Canada and North America (1690-1763). The emblem is also seen on French uniforms, our allies, as well as the British whom we were fighting against, during the American Revolution (1775-1783). The United States was only 36 years old when our military unofficially adopted the flaming bomb as an insignia, shortly after the War of 1812. It became the official emblem of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps in May of 1833. Just three years later in 1836 the American defenders at the Alamo faced the Mexican Army under the command of Santa Anna. During this famous battle the Mexican Grenadiers wore the small exploding bomb insignia on their shako (hat). There is an example of this emblem on display at the Alamo museum down town San Antonio.

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), ordnance troops from both the Confederate and Federal forces wore our symbol with pride. AFCOMAC has a beautiful example of a WWI US Army ordnance NCO uniform on display. The bursting bomb was part of the rank insignia. Before the out-break of World War II (1941-1945), the flame on the U.S. insignia was larger and had more of a European appearance in contrast to the current emblem which is more streamlined. In the U.S. Marine Corps, there is a variation of the symbol known as the gunner’s emblem. It is worn by Master Gunnery Sergeants in the Marine Corps and officially called the bursting bomb.

During WWII, our symbol appeared in a fascinating place. Woman Ordnance Workers (WOW’s) were employed in munitions factories all over America producing weapons and ammunition in support of the war effort. Part of their uniform was a bright red bandana with white flaming bombs- the distinctive WOW trademark.

At one time in our military history, this was worn as a rank insignia with the Coast Guard and Navy as Chief Mariner gunner. The flaming or bursting bomb is the oldest military insignia used today in our armed forces and is one of the oldest still used throughout the world.

It is truly an international symbol and just may be the single most widely used uniform emblem in the history of military heraldry.

At present, the USAF does not officially recognize the bursting bomb insignia as any part of our uniform except on an occasional unit patch. Our symbol has been an unofficial symbol since the days ex-Army Ammo troops reenlisted or transferred over to the newly formed Air Force just after World War II (1947). Since that time, it has been a familiar rallying point for Air Force AMMO troops stationed or deployed in every corner of the globe.

Although our duty as a 2WO in the U.S. Air Force in the present military era has us maintaining all manner of explosives from small arms bullets to sophisticated guided weaponry, the small ordnance insignia should remind us of our humble beginnings. Let it remain our rallying point during some of the rough times we all face in the daily, sometimes hectic duties of our bomb dumps. The next time you see our symbol of the flaming or bursting bomb, reflect back and consider its significance to our AMMO heritage. It is a symbol which holds fast to traditions. Our badge deserves a prominent place in the history of warfare which we are all proudly part of. Be proud of your unique duty and as members of the AMMO profession.

CONTINUE THE AMMO PRIDE

Paul B. Smith, CMSgt, USAF (ret)

Hill AFB, Utah

1994 First edition, Beale AFB, California (AFCOMAC)

1997 Second revised edition, Misawa AB, Japan

2000 Third revised edition, Dyess AFB, Texas

2001 Forth revised edition, Incirlik AB, Turkey

2003 Fifth revised edition, Incirlik AB, Turkey

2005 Sixth revised edition, Hill AFB, Utah

Copyright ? 2005 Paul B. Smith

All artwork copyright ? 2005 Paul B. Smith

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Rosignoli, Guido. World Army badges and Insignia Since 1939. Dorset: Blandford Press Poale, 1983.

2. Kerrigan, Evans E. American Badges and Insignia. New York: The Viking Press, 1967.

3. Tracy, Harry F. “Grenadiers Elite Status.” Military History Magazine. (Aug. 1986). Weaponry article.

4. The Soldier of Fortune, a book compiled from Soldier of Fortune Magazine articles. Wieser and Wieser, New York, 1986.

5. Kindersley, Dorling. The Visual Dictionary of Military Uniforms. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1992.

6. Fowler, William. Military Insignia. London: Chartwell Books Inc, 1993.

7. Sterling, Keir B. PhD. U.S. Army Ordnance History. Date unknown